Since the end of the last ice age, the Bay of Sept Îles has been home to nomadic groups, hardy fisherfolk and bold entrepreneurs. It has seen cottages crop up along its shores that grew into villages, then towns, to become a full-fledged city serving an entire region of Quebec. As new facilities were built to accommodate burgeoning industries, a small village harbour slowly grew to become one of the largest seaports in North America. Enjoy this brief look back at the Port of Sept-Îles.

CIRCA 4,000 BCE

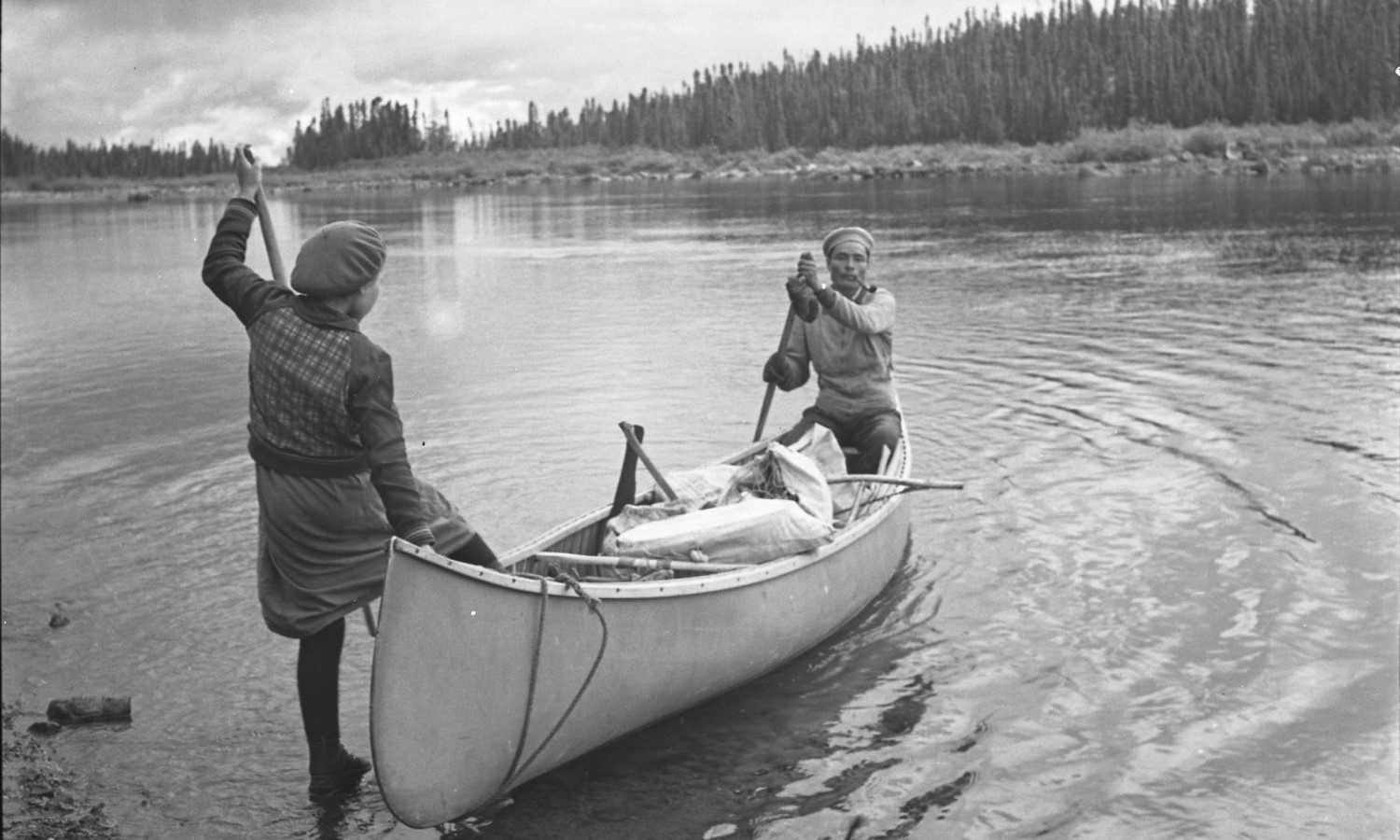

The tribes involved, now recognized as the ancestors of the Innu Nation, only frequented the coast in summer. Dependent on hunting and gathering, they migrated north in the fall, following the herds of sacred caribou they relied on to survive the harsh winters.

In all likelihood, the Innu’s ancestors were not the only ones in the area at the time. Mi’kmaq-related groups are also believed to have explored the Middle North Shore, probably reaching the Bay of Sept-Îles, which they called Chichedek. Known for their remarkable navigational skills, the Mi’kmaq set out from the Gaspé Peninsula in 8-metre-long boats, travelling up to 60 kilometres in a single day. It is quite likely, though, that the Innu’s relations with these adventurers were less than friendly.

1520

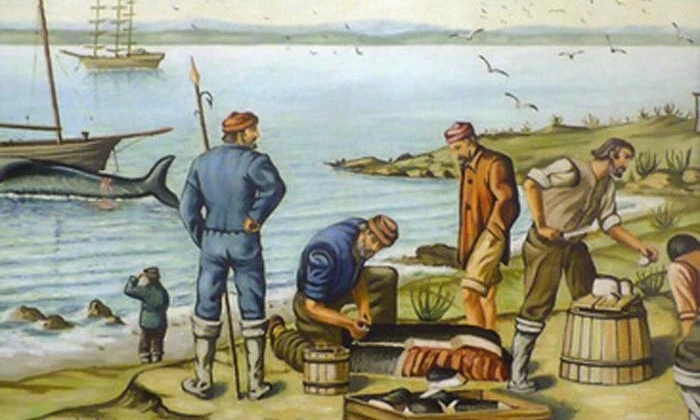

It is unclear whether Basque fishermen visited the Bay of Sept-Îles in the 16th century. Pointe-aux-Basques, located east of the bay, as well as Grande Basque and Petite Basque Islands, actually owe their names to more recent whaling expeditions during the French colonial regime. These expeditions were led by the Daragory brothers, Basque fishermen from Spain who hunted whales in the Sept-Îles Archipelago from 1739 to 1742.

1535

Although the bay may have been visited by European explorers and fishermen long before Cartier’s arrival, there is no archaeological evidence to prove it. Similarly, there is no proof that the Vikings or 16th century Basque fishermen visited the region. Based on current knowledge, Jacques Cartier was the first European confirmed to have explored the Bay of Sept-Îles.

1651

1652

1661

1673

It is unclear, however, when the Sept-Îles trading post was actually founded. Archaeological excavations in the 1960s revealed that the trading post was located in the Bay of Sept-Îles in a cove near the mouth of the Du Poste River, a sheltered spot providing an ideal harbour for small vessels.

1693

Pieces of the wreck still lie at the bottom of the bay, and Corossol Island bears the name of the shipwrecked vessel to this day

1759

Contemporary documents covering local history make reference to two other acts of destruction preceding Wolfe’s attack. The first supposedly occurred during the First Intercolonial War in 1692, while the second was carried out by British marauders some 30 years later. However, based on an analysis of those documents and the archaeological records, the authenticity of both events cannot be established at this time.

1761-1763

1786

In the 1970s, Harrison’s report and the work of archaeologist René Lévesque were used to reconstruct the Sept-Îles trading post as it was in 1786.

1840

~ 1865 - ~1900

At that time, people built homes wherever they liked, in the places they found most suitable. Their preference was for medium-sized structures with pointed roofs and walls covered in cedar shingles. Barns and kennels were also constructed, along with wells since there was no community water system. Horses were raised, of course, in addition to chickens, pigs and cows. The bay also provided an abundance of hay for livestock feed.

Despite the Roman Catholic clergy’s efforts to promote agriculture, the Sept-Îles economy was based primarily on fishing, as well as on the fur trade, which was still in full swing. Farming was undertaken to feed family members, with no commercial aspirations.

1866-1870

The avid geographer and geologist meticulously observes the area with a Rochon telescope, draws up nearly a hundred maps, scouts out a number of iron ore deposits and records all his discoveries in a thick journal. Three years later, the incredible amount of data Babel collected is used to compile the first map of the interior of Labrador.

Babel’s journal included this admiring account of the Innu and Naskapi peoples and their lands: “They give us reports on all aspects of the terrain, each twist and turn of the lakes and rivers. They know every tree in the forest.”

1891

Benjamin and Clarisse were the only survivors of the tragedy. The bodies of all the victims were recovered, except for those of Joseph and Célanire Montigny, aged 8 and 11 respectively. Benjamin later said that he saw his two cousins being swept out into the open water by the ruthless force of the waves, holding hands in the face of their demise.

Hailed as a local hero, Bujold would serve his community honourably as a justice of the peace and a city councillor before his death on May 10, 1965.

1892-1895

1895

1898

1901

On the night of November 20, a storm caught the postal ship Saint Olaf by surprise, which crashed onto rocks near the island of Grosse Boule. In addition to pieces of the wreckage, a woman’s frozen corpse was found in a snowbank, next to a mail bag. She was wearing a life jacket over her nightgown.

1904

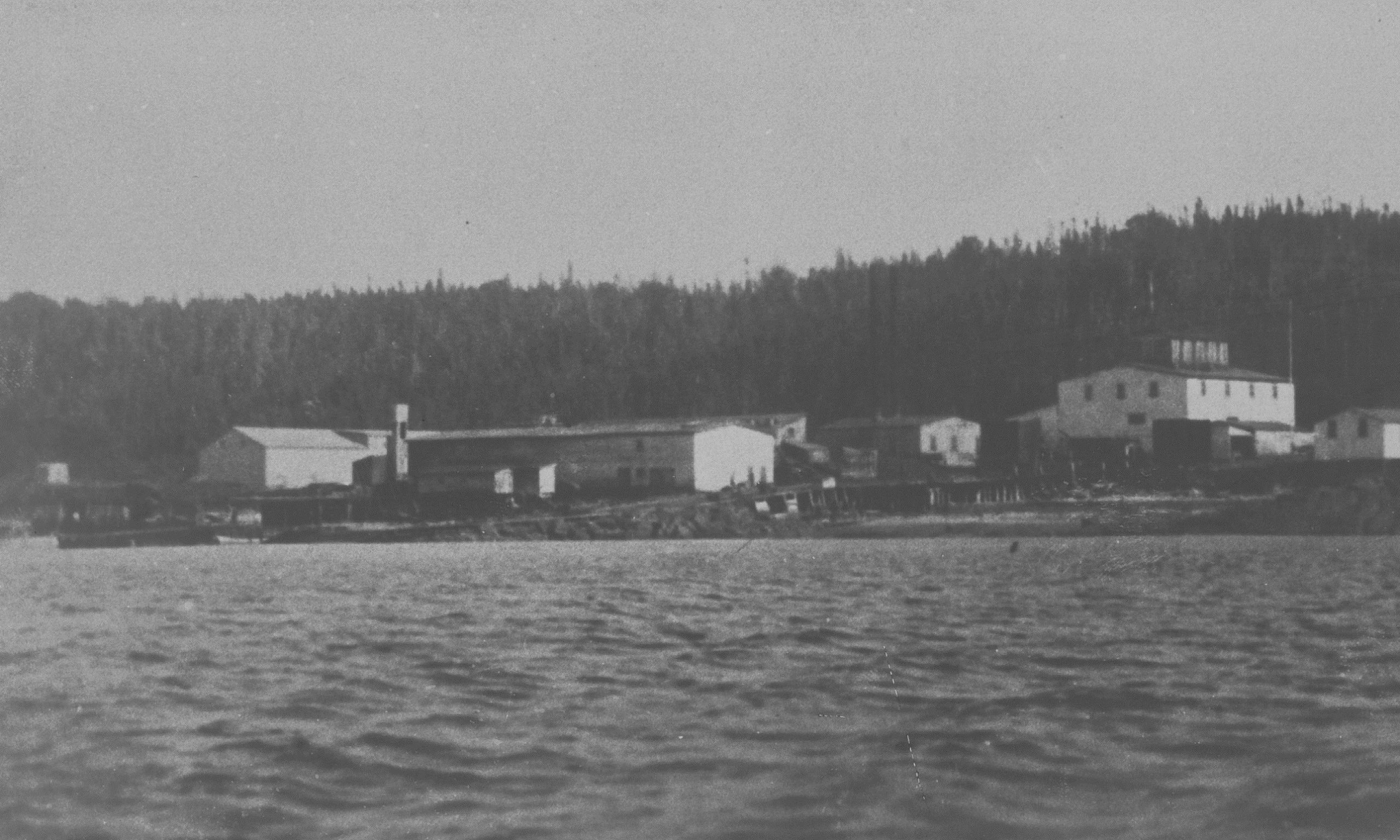

The North Shore Power, Railway & Navigation Company, recently founded by the Clarke brothers, built the area’s first industrial wharf in Pointe-Noire. It eventually became known as the Clarke City Wharf.

1905

1906

1908

The North Shore Power, Railway & Navigation Company officially founded Clarke City and began construction of the SM1 hydroelectric facility.

Despite its remarkable success, the Quebec Steam Whaling Company did not renew its operating licence and its owners would soon liquidate it.

v. 1910

The ice house was located near the current site of Monseigneur-Blanche Dock. In spring, it was filled with snow, which was packed down using poles. Containers of salmon were then stored there prior to shipment.

Arcand’s ice house fell into disrepair due mainly to the construction of a refrigerated warehouse in Sept-Îles. It would eventually be demolished, but the nearby dock, used by fishing boats and pleasure craft, known as the Arcand Wharf, still bears witness to his memory.

1911

A group of Norwegian investors resumed whaling in Sept-Îles, operating as the Canadian Steam Whaling Company.

To meet the local fishing industry’s growing needs and to finally facilitate the delivery of mail and goods of all kinds, the Sept-Îles municipal council convinced the federal government to build the bay’s first public dock, known as Saint-Joseph de Sept-Îles. It is now known as the Vieux-Quai (Old Dock).

1914

A violent storm destroyed the Vieux-Quai, and the local community would have no public dock access for two years.

The outbreak of the First World War in Europe forced the Canadian Steam Whaling Company to close temporarily. Its Norwegian owners set sail for Europe in the fall and never returned. What became of them remains a mystery to this day. A German submarine was rumoured to have sunk their ship, although it is more likely they simply abandoned the company since whale oil was regarded as wartime contraband.

1916

The old whale oil factory and its wharf were dismantled.

1929

1932

1936

The Labrador Mining and Exploration Company sends geologist Joseph Arthur Retty to Labrador to lead a prospecting campaign. With the help of Mathieu André, an Innu trapper from Sept-Îles, Retty finds a high-grade deposit at Lac Sawyer, about 100 km from Schefferville—a discovery that sparks the mining industry’s interest in Labrador iron.

1947

In July, a group of eight financiers travelled to Labrador to assess the mining exploration underway. Among them was the president of the M.A. Hanna Company, George Humphrey, who was riled by the lack of gold deposits in this part of the country and demanded new discoveries—the more miraculous, the better! On July 27, the group was taken to Ruth Lake, where a huge outcropping of iron ore was visible at the foot of a high cliff. Excited by this unique geological phenomenon, Humphrey exclaimed: “This is the first time in my life I’ve seen a wall of iron ore shooting out of the earth like that. I don’t think we should let all that wealth slip away.”

1949

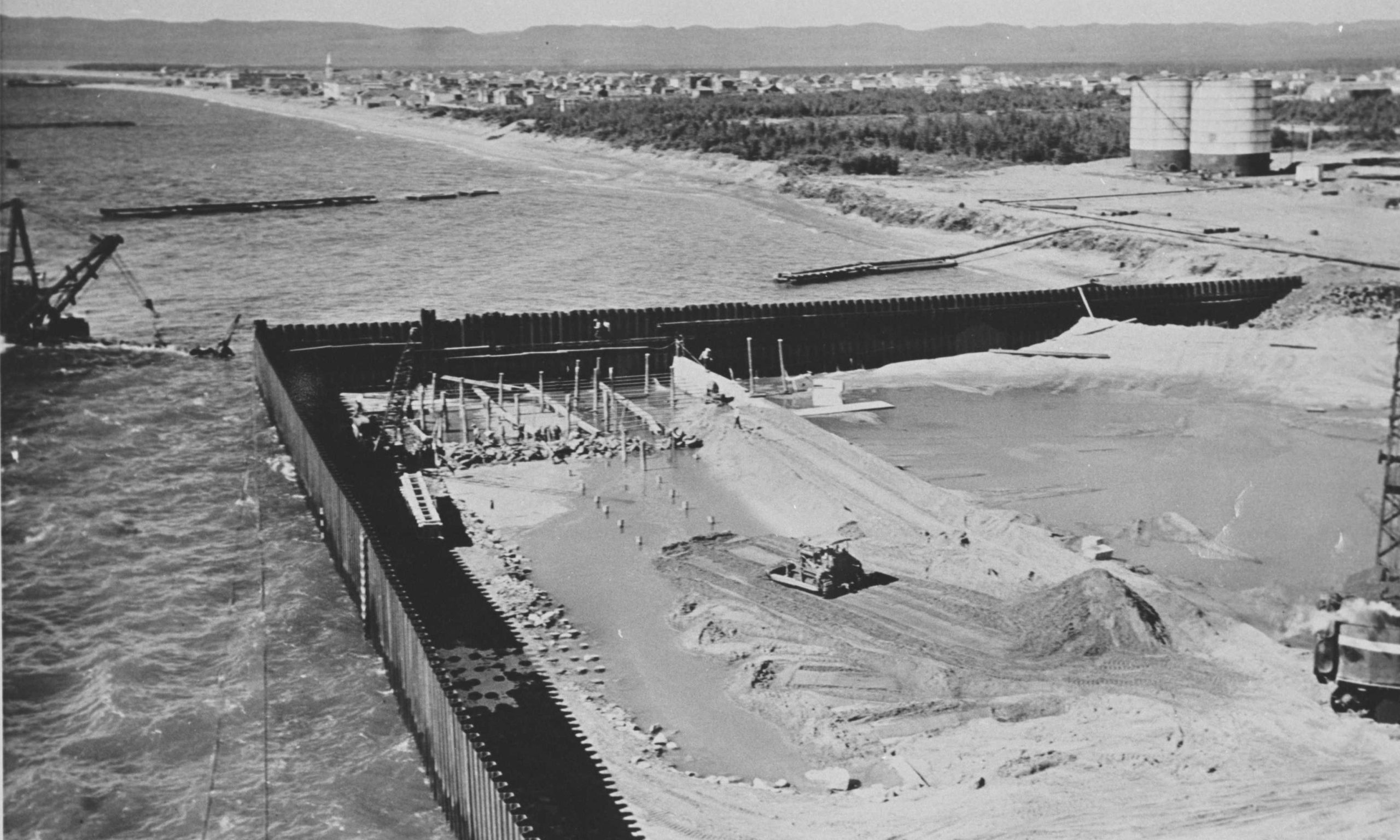

The U.S. consortium invested $375 million in various essential projects, including building the town of Schefferville, a railway linking the mining site to the St. Lawrence River, and a transshipment port terminal for maritime shipping. Sept-Îles was selected as the site of the ore-shipping port. This momentous decision sealed the city’s industrial destiny.

1950

In Sept-Îles, the Vieux-Quai was overflowing with food supplies, materials, tractors, drillers, graders, diggers, etc. It was a particularly grandiose scene for a village that was still a tiny fishing port.

1952

1953

1954

On July 31, the first ship was loaded at the IOC’s port facilities. A crowd gathered in Sept-Îles for the official inauguration. During the ceremony, Premiers Duplessis and Smallwood took part in the symbolic loading of the ore. The SS Hawaiian then left the Port of Sept-Îles bound for Philadelphia with 20,500 tons of iron ore on board.

To reduce congestion at the Vieux-Quai, the federal government built the fourth public dock not far from Pointe-aux-Basques. This dock was 244 metres long and 8.5 metres deep at low tide. It was dubbed the Monseigneur-Blanche dock in honour of a bishop who lived in Sept-Îles from 1906 to 1916.

The village of Sept-Îles, now a city boasted its own water system and a new electricity grid.

1958

1959

On June 19, the Royal Yacht Britannia arrives at the IOC dock and departs the next day carrying Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, bound for home after spending a few days in Sept-Îles and Schefferville. The royal couple headed to Montréal for the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway on June 26.

1960

1961

Imperial Oil, the bay’s main supplier of gasoline and fuel oil, built a dock between the Pointe-aux-Basques and Monseigneur Blanche docks for unloading petroleum products.

A second business consortium formed the Wabush Mines company and began to develop iron ore deposits in Labrador.

1962

1965

1967

The Clarke City Wharf fell into disrepair after the closure of the paper mill, its main user. Over the years, the bay would swallow up the dock’s wooden frame, and today only a piece of the rock foundation is still visible.

1973

1973-1983

1974

1977

On August 1, the National Harbours Board acquires the Imperial Oil Dock and renames it the Pétroliers Dock.

On December 6, after three years of negotiations with Wabush Mines, the National Harbours Board acquired several hundred hectares of industrial land in the Pointe-Noire district. A few years later, some of this land would be used to build the largest aluminum smelter in the Americas.

1980-1985

The iron market’s collapse led to the closure of the Sept-Îles ore concentration and pellet plants, and some 500 IOC employees lost their jobs. This ushered in a period of serious demographic decline over the following years. Total employment at the Port of Sept-Îles and local mining companies went from 4,000 people in 1976 to 2,500 in 1985. Disgruntled workers moved away, the residential vacancy rate rose to 25%, and real estate values plummeted by 30%. Radio-Québec’s regional office, Radio-Canada’s TV production facilities, and the Moisie military base all closed down.

1982

1983

On September 23, Ports Canada began work on a new facility at Brochu Cove in the Pointe-Noire district, across from land acquired from Wabush Mines by the National Harbours Board six years previously. An eight-km stretch of road was built with a water main running alongside, and plans were drawn up for a new dock.

1984

Ports Canada awards a $10 million contract to build the new dock at Pointe-Noire.

1986

1989

On September 1, the Aluminerie Alouette consortium held the groundbreaking ceremony for its new facilities, with Premier Robert Bourassa in attendance. The company went on to become the main user of La Relance Wharf, and its first ton of aluminum was produced in 1992.

To better support the local fishing industry, a harbour was built between the marina and the Monseigneur-Blanche Dock.

On October 7, the Canadian Forces' 22nd Naval Reserve Division, HMCS Jolliet, was inaugurated in temporary facilities.

1990

1993

1994

1998

The new Canada Marine Act was enacted, dissolving the Canada Ports Corporation (Ports Canada) and replacing it with 15 autonomous Canada Port Authorities. Operating at arm’s length from the federal government, these new non-profit organizations took over management of ports deemed essential to Canada’s economy.

1999

The federal government transferred responsibility for the bay’s federal port infrastructure, with the exception of the fishing harbour and the Vieux-Quai, to SIPA (also known as the Port of Sept-Îles). The new administration was tasked with making the assets profitable, remaining financially self-sufficient and ensuring global competitiveness, as if it were a private company. The people of Sept-Îles were now in charge of their port, in keeping with a uniquely local vision.

2004

2007

2010

On October 4, the Port of Sept-Îles, the City of Sept-Îles and the Innu Takuaikan Uashat mak Mani-Utenam (ITUM) band council inaugurate the Cruise Ship Dock and it welcomes its first ship, the Norwegian Spirit. The facility, 315 metres long and 11 metres deep, is located at Monseigneur-Blanche Terminal. By the end of 2019, nearly 50,000 cruise ship passengers and crew members had come ashore at Sept-Îles.

2011

2012

The iron market collapsed again, due in part to a Chinese market slowdown and strong competition from Brazil and Australia.

2013

When Cliffs Natural Resources refuses to let other companies have access to the railway leading to the Multi-user Dock, the Port of Sept-Îles insists the stretch in question should be subject to the Canada Transportation Act like the rest of the Arnaud Railway, kicking off a 2-year legal battle.

The City of Sept-Îles, the Port of Sept-Îles and their partners establish the Environmental Observatory for the Bay of Sept-Îles, an innovative approach to characterizing the bay’s ecosystem. The large-scale study, locally commissioned by the Northern Institute for Research in Environment and Occupational Health and Safety (INREST), aims to provide a broad understanding of the bay and a better grasp of the impact of human activity on its shores.

The Bay of Sept-Îles faced an unprecedented environmental disaster. On the morning of September 1, a valve was left open after a fuel transfer to Cliffs Natural Resources. The resulting tank overflow led to several hundred thousand litres of heavy fuel oil being spilled. Because of a sealing problem in the holding pond, some of the toxic hydrocarbons seeped into the bay. In addition to spending nearly $25 million to clean up the site, Cliffs acknowledged its negligence and paid an $821,000 fine.

2014

2015

However, two major obstacles delayed the dock’s commissioning by several years. They included the bad state of the iron market and various obstacles imposed by Cliffs Natural Resources, which owned the railway infrastructure serving the multiuser dock.

After 2 years of litigation with the Port of Sept-Îles, Cliffs Natural Resources gives up the fight and cedes access to its Pointe-Noire rail facilities, marking a huge milestone in the commissioning of the Multi-user Dock.

On May 20, Cliffs filed for bankruptcy and, as part of the legal liquidation process, the provincial government, via Investissement Québec, acquired the company’s industrial and railway facilities at Pointe-Noire.

2016

One of SFP Pointe-Noire’s main goals was to promote the economic diversification of Sept-Îles and the region, with all profits being reinvested in the company and the local community. The company’s shareholders do not receive dividends.

Tata Steel loads its first shipment of iron ore at the Pointe-Noire Terminal in October. The Cielo Europa leaves Baie des Sept Îles laden with 100,000 tonnes of ore.

The Port of Sept-Îles acquired Block Z, which encompassed some 400 hectares of vacant land stretching for 5 km along the Aluminerie Alouette access road.

2017

SFP Pointe-Noire signed a long-term service contract with Quebec Iron Ore, which relaunched the Bloom Lake mine near Fermont. That year, almost 1 million tons of ore passed through SFP Pointe-Noire’s facilities.

2018

SFP Pointe-Noire completes the construction of a conveyor system linking the Multi-user Dock to the rest of the Pointe-Noire industrial facilities and signs a long-term service agreement with Tacora Resources.

The commissioning is inaugurated on March 26 and the Multi-user Dock welcomes its first ship, the M/V Magnus Oldendorff. The bulk carrier leaves the Port of Sept-Îles for Qingdao, China, carrying nearly 200,000 tonnes of ore mined at Fermont by Quebec Iron Ore.

On December 3, after 4 years of research by a multidisciplinary team of more than 40 environmental experts, the Environmental Observatory for the Bay of Sept-Îles releases its final report. The findings will allow the Port to better understand the impact of its activities and adapt its practices accordingly.

2019

To mark its 20 years of autonomy, the Port also teams up with Microbrasserie La Compagnie to craft a commemorative beer, Pointe aux Basques. For every Pointe aux Basques beer sold, the microbrewery and the Port donate to a local community organization.

2020

The Port of Sept-Îles began repair work at the Pointe-aux-Basques Dock in preparation for its reopening.

2021

Three mining companies operating in Schefferville, Fermont, and Labrador use the services of SFP Pointe-Noire, which employs some 250 people and handles over 10 million tons of merchandise each year.

YOUR CRUISE ON THIS PAGE ENDS HERE.

CHOOSE A NEW DESTINATION!

The Sept-Îles Port Authority is a non-governmental organization run by people from Sept-Îles who prioritize local development.

Explore North America’s largest mineral port facilities from wherever you are using 360° immersive technology.

Take a look at the 9 docks that make up the 5 terminals owned and operated by the Port of Sept-Îles.